Cabo Pantoja|Sta Clotilde|Iquitos|Amazon|Yurimaguas|Tarapoto|Cuispes|Chachapoyas|Carajía|Sonche|Cajamarca|Huanchaco|Chan Chan|Trujillo|Huacas|Huaraz|Santa Cruz|Lima|Nazca|Cusco|Machu Picchu|Maras|Limatambo

(Each destination follows this pattern: English text 1st, photos 2nd, Polish text 3rd/najpierw po angielsku, potem zdjęcia, potem po polsku)

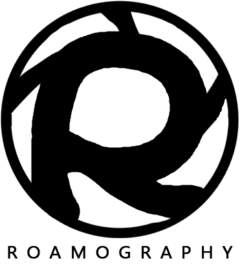

We navigate into Cabo Pantoja… This is our first stop in Peru, welcoming us with colourful houses in front of which a slow village life is happening: someone is cutting someone’s hair, someone is playing bingo, kids are running around… All bathed in the afternoon sun, inviting us to explore Cabo Pantoja and its surroundings. Attractions include a military base (from which we are politely asked to leave), beer shops (why not?), a disco (no one dances here, just our group of foreign freaks) and a restaurant (you have to make an appointment and wait about two hours for a meal) and, of course, the stately and photogenic Rio Napo, which we will float down early tomorrow morning.

P.S. Before you get caught up in exploring Cabo Pantoja – first go to the immigration office to get your Peruvian visa. And don’t give any credence to the opening hours given on the Ecuadorian side, in our case they had nothing to do with reality and we nearly arrived after the office closed!

P.S. 2 It’s a good idea to go to sleep before they switch off the electricity at night (and they 100% will!), so as to avoid noticing how unbearably stuffy it gets in the hostel room without a working fan.

Cabo Pantoja

Wpływamy do Cabo Pantoja… To nasz pierwszy przystanek w Peru, witający nas kolorowymi domkami, przed którymi toczy się powolne wioskowe życie: ktoś komuś strzyże włosy, ktoś gra w bingo, dookoła biegają dzieciaki… Wszystko skąpane w popołudniowym słońcu, zapraszającym nas do zwiedzenia Cabo Pantoja i okolic. Z atrakcji jest tu baza wojskowa (z której terenu zostajemy grzecznie wyproszeni), sklepy z piwem (czemu nie?), dyskoteka (nikt tu nie tańczy, tylko nasza grupka zagranicznych dziwolągów) oraz restauracja (na posiłek trzeba się wcześniej umówić i poczekać jakieś 2 godziny) i, rzecz jasna, dostojna i fotogeniczna Rio Napo, którą spłyniemy jutro wcześnie rano.

P.S. Zanim się wciągniecie w zwiedzanie Cabo Pantoja – najpierw wybierzcie się do biura imigracji po peruwiańską wizę. I nie dawajcie wiary w godziny otwarcia podane po stronie ekwadorskiej, w naszym przypadku nie miały nic wspólnego z rzeczywistością i mało brakowało, a dotarlibyśmy po zamknięciu okienka!

P.S. 2 Dobrym pomysłem jest zaśnięcie zanim w nocy wyłączą prąd (a wyłączą na 100%!), żeby uniknąć zauważenia, jak niemożebnie duszno jest bez działającego wentylatora w hostelowym pokoju.

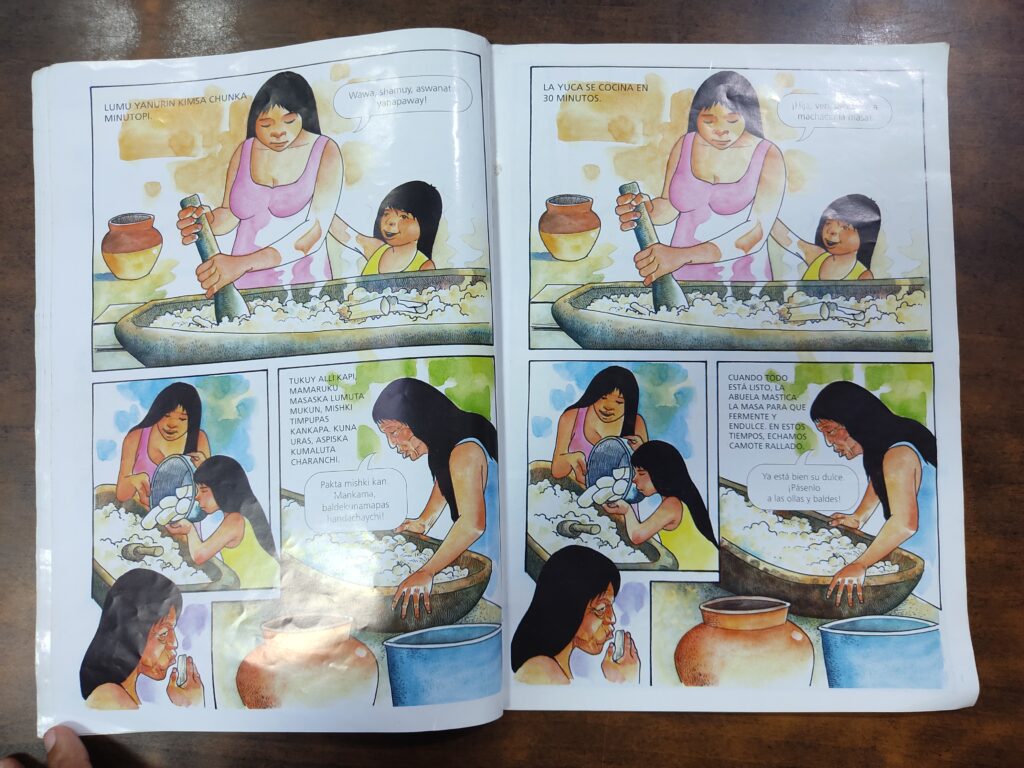

It’s a dark night, the village is all quiet… Slightly sleepy, we load into our boat, which will carry a colourful crowd as well as a few chickens and a heap of bananas and other produce to be distributed in the villages we will pass by. And these villages look very pleasant – usually a few wooden huts on poles, women strolling along the river bank with children in their arms, sometimes the bustle coming from a school building… We pass boats going between villages, and on them people focused on their river-jungle business. In one of the towns we make a lunch stop, during which we are treated to masato, a traditional yucca-based drink that obtains its unique flavour by being chewed by toothless old ladies, spat into a bowl and waited for the whole thing to ferment. The tradition is said to be over a thousand years old, so I guess they have this technology right.

We arrive in the town of Santa Clotilde for the night, where the race for the best rooms begins – apparently there are more passengers than the local accommodation base can handle. The locals know well where to rush to, we lag a little behind and so the only thing we manage to get is a half-flooded room in a slightly sinking building standing askew. But hey, there are those who have worse than that: a couple of our fellow travellers end up sleeping on the balcony, others decide to stay the night on the hot and steamy boat. We get up in the middle of the night and set off outrageously early for the rest of the trip.

Santa Clotilde

Ciemna noc, wioska śpi, lekko zaspani ładujemy się do naszej łodzi, w która, oprócz pasażerów, wieźć będzie także kilka kur oraz górę bananów i innych produktów, które zostaną rozdystrybuowane po mijanych wioskach. A wioski te prezentują się nad wyraz sympatycznie – zazwyczaj to kilka drewnianych chat na kijach, przechadzające się po nabrzeżu kobiety z dziećmi na rękach, czasem gwar dobiegający z budyneczku szkoły… Mijają nas łodzie, kursujące między wioskami, a na nich ludzie zajęci swoimi rzeczno-dżunglowymi sprawami. W jednej z osad robimy sobie postój obiadowy, podczas którego zostaję poczęstowany masato, tradycyjnym napojem na bazie juki, który uzyskuje swój niepowtarzalny smak poprzez przeżucie tejże juki przez bezzębne starsze panie, wyplucie do miski i odczekanie aż całość sfermentuje. Ponoć tradycja ta ma już ponad tysiąc lat, więc należy uznać, że ten proces technologiczny się sprawdza.

Na noc docieramy do miasteczka Santa Clotilde, gdzie rozpoczyna się wyścig po najlepsze pokoje – najwyraźniej pasażerów jest więcej, niż może udźwignąć tutejsza baza noclegowa. Lokalsi dobrze wiedzą, dokąd należy gnać, my zostajemy trochę z tyłu i przez to jedyne, co nam się udaje dorwać, to połowicznie zalany wodą pokój w lekko podtopionym budynku. A i tak nie mamy co narzekać, paru naszych współtowarzyszy podróży ostatecznie śpi na balkonie, inni decydują się pozostać na noc na dusznej łodzi. Wstajemy w środku nocy i skandalicznie wcześnie ruszamy w dalszą część trasy.

The next day we arrive in Mazán, where the Napo River twists into an arc that it is not worthwhile for boats to circumnavigate, so we take a shortcut, jumping onto a tricycle to the other end of the town (beware of scammers, ask about the price of transport beforehand), where another barge is already prepared to transport us to Iquitos. This will be our first few hours on the Amazon River….

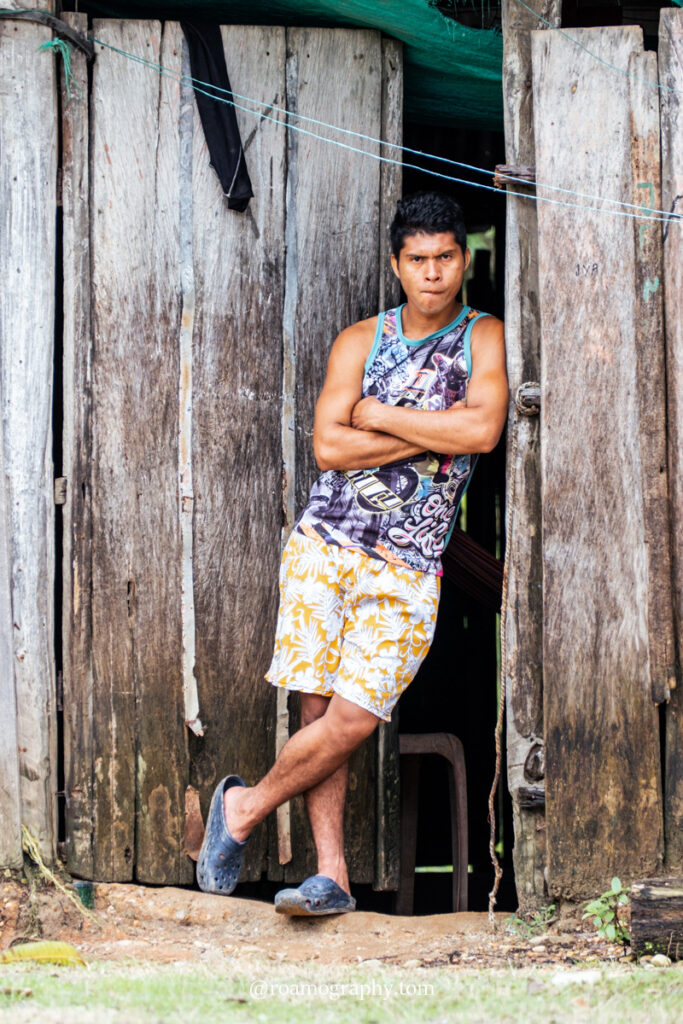

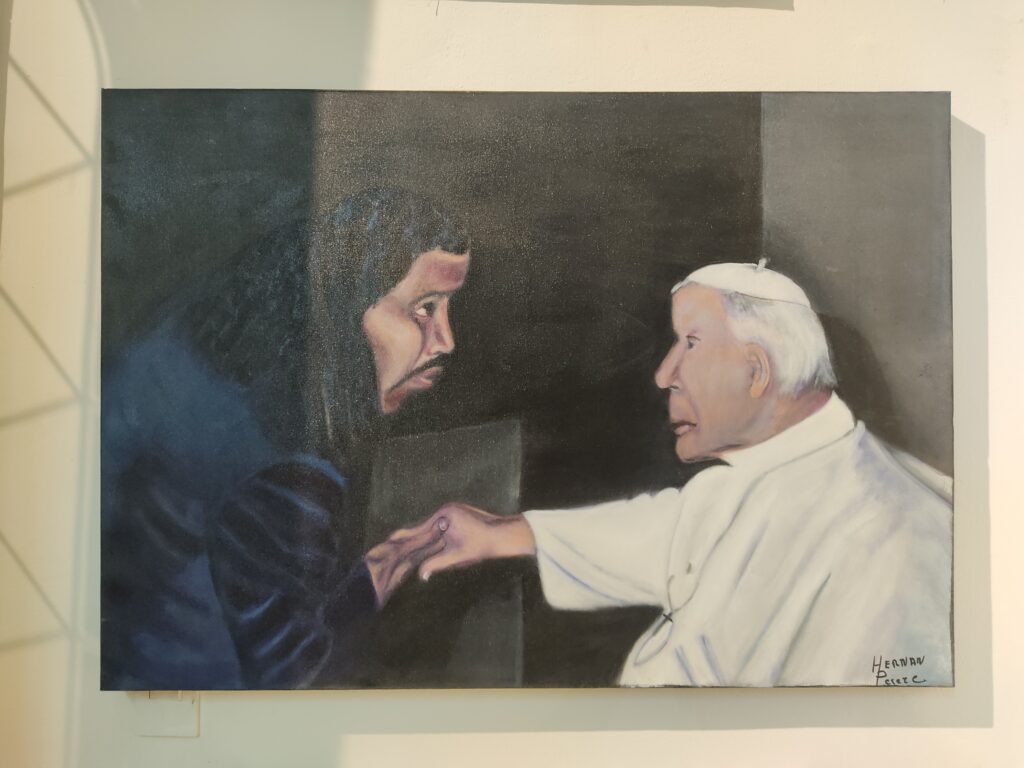

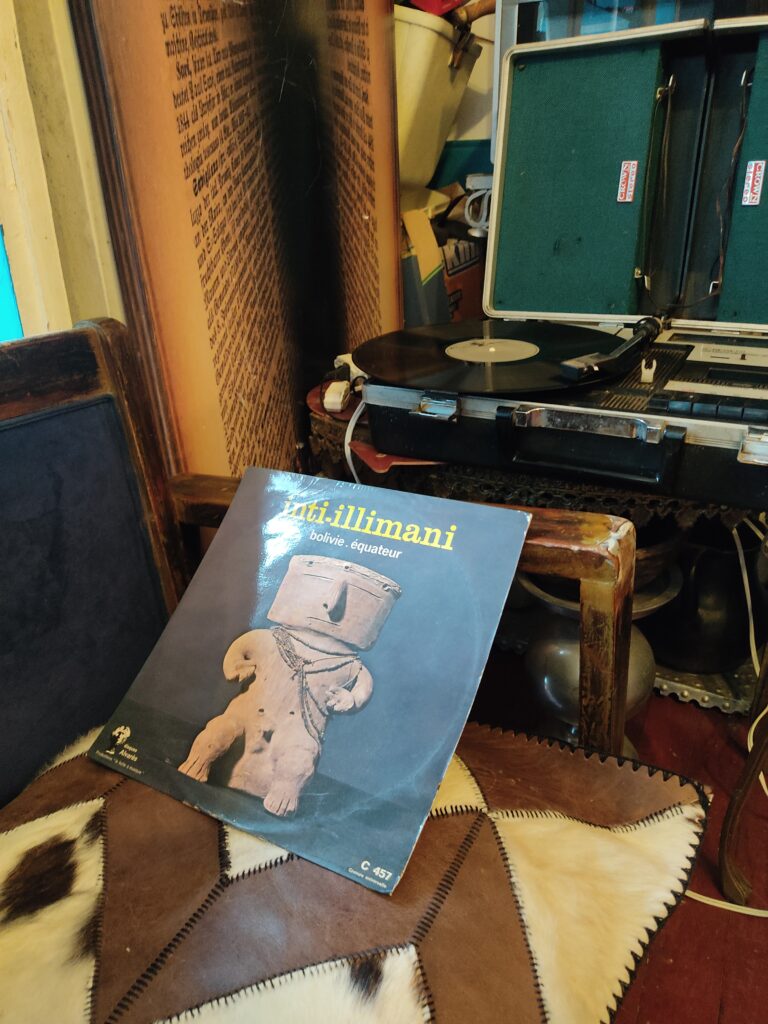

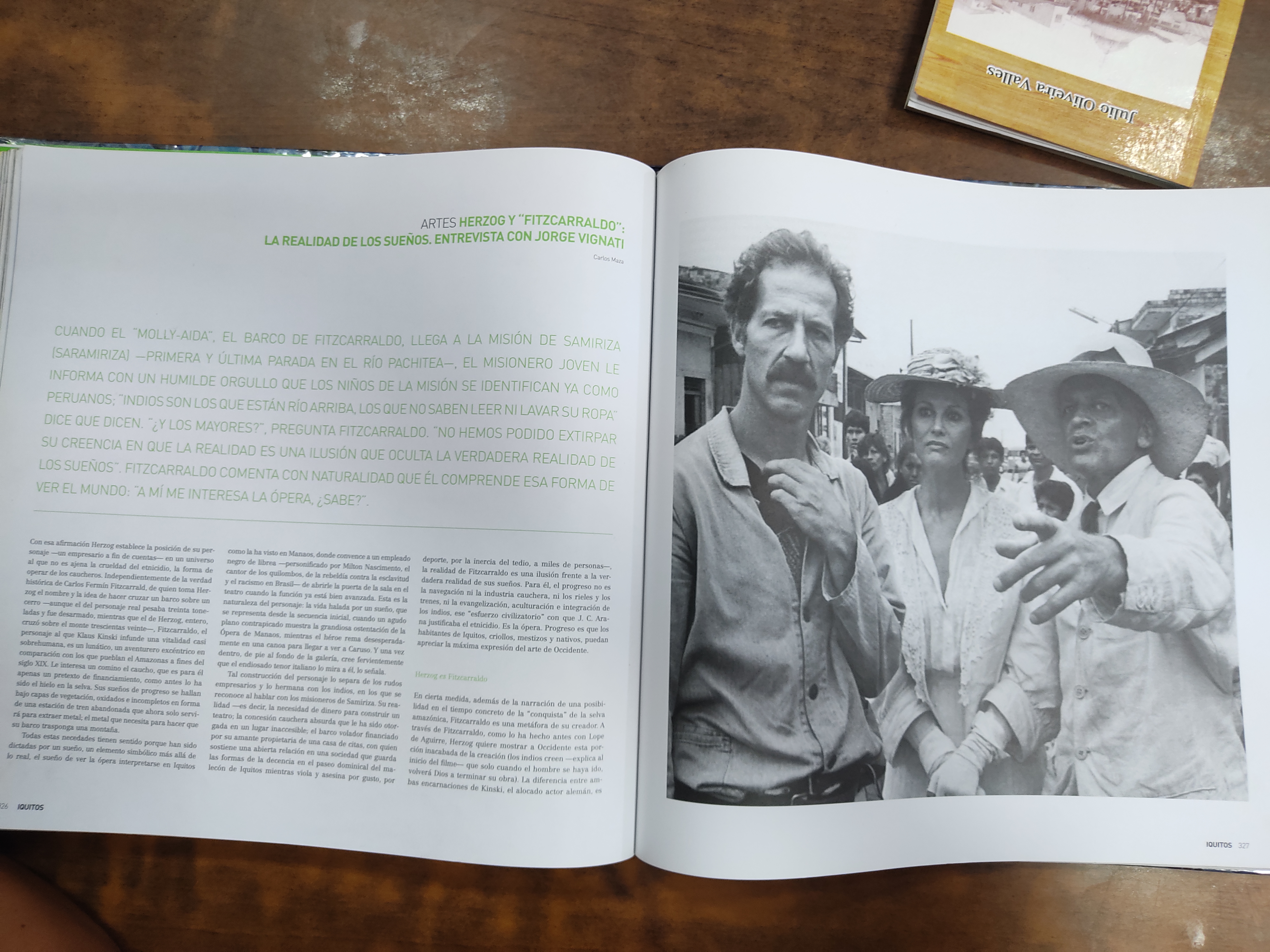

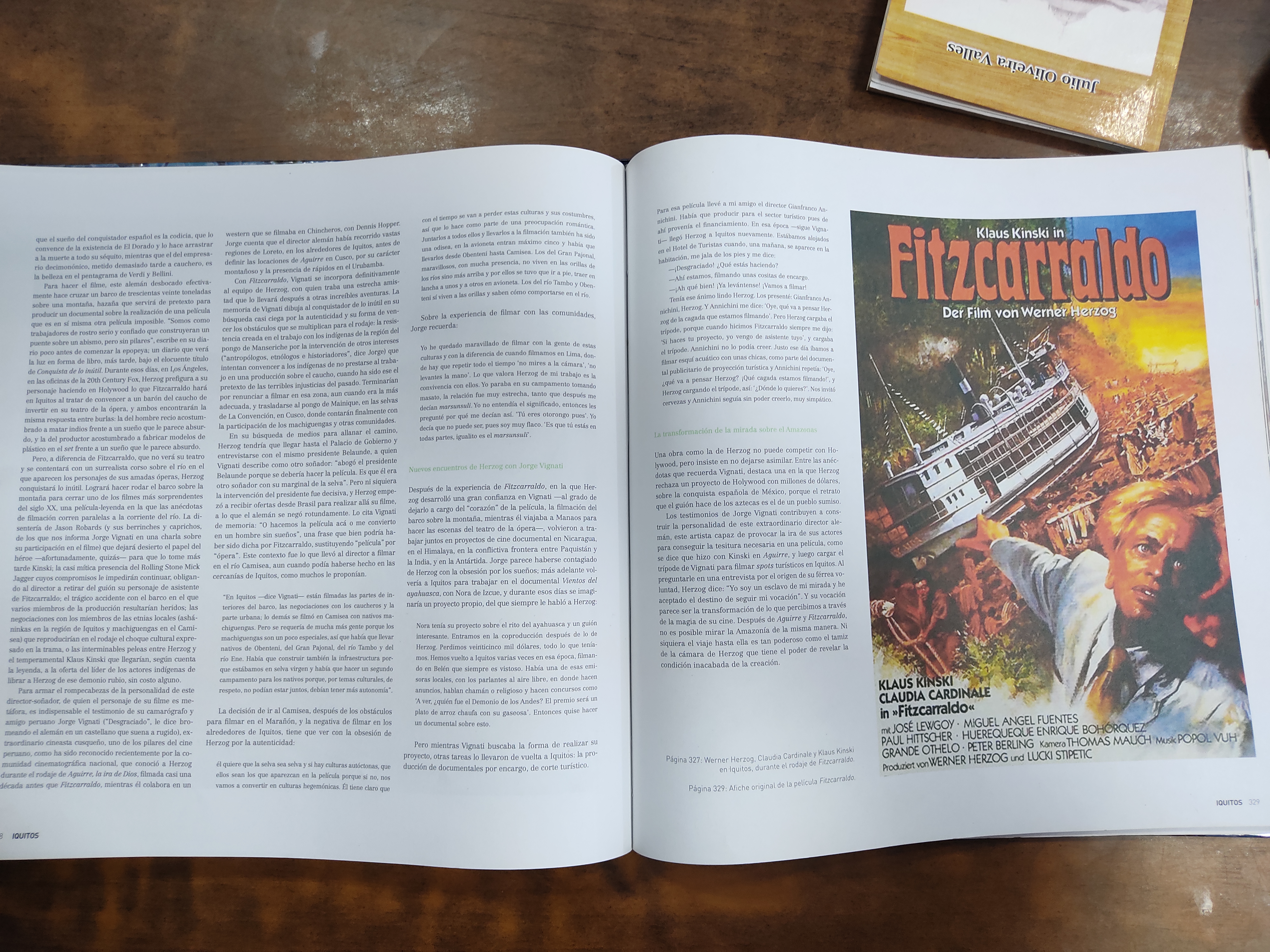

Iquitos is the largest city in the world reachable only by water or air, not connected to the rest of Peru by any road (it would be very difficult to carve through the dense Amazon forest), it is the city that made into one of Herzog’s cult films, “Fitzcarraldo” (which you can read about in several books available in the city library; you can also scan Iquitos in search of shots from the film), a symbol of the rise and then fall of the rubber industry, with the fabulous fortunes of the rubber barons whose names still ornate the streets here and the inhumane exploitation of the local population (I encourage you to find out more about these themes at the Museo Etnográfico Amazónico)… In short, it is a legendary city that I promised myself to visit a long time ago and finally fulfilled that promise.

The chaos of the harbours, the colourfulness of the markets (the infamous ‘magic’ section, where weird specialities made from crocodiles, turtles and other – endangered and protected – animals are traded), the decaying townhouses that try to grow old with dignity, reflecting on their luminous past, a promenade overlooking a tin-roofed, huge district of the poor, built up densely with houses on stilts, often without running water, suspended over the marshes in the dry season and the river in the rainy season…. There’s the ghost of an unfinished hotel, haunting the central Plaza de Armas, right next to the Casa de Fierro, a stylistically outdated metal structure, there’s a cinema wildly besieged at weekends, there’s the constant whirr of excessive numbers of moto-taxis

by day and a precarious looking over your shoulder at night….

Our base for exploring the city is Casa del Paucar, an oasis of relative calm (the furious whirring of motorbikes and scooters can still be heard here, as these vehicles are just countless; cars are harder – and more expensive – to bring here). The staff here are very friendly and there are a lot of Israeli young people who sometimes need to be reminded that they are not alone;)

A pleasant surprise is a meeting with a Polish violinist based in Iquitos, with whom we almost manage to shoot a music video, but in the end we have to postpone the project until next time… Near the town there is the Centro de Rescate Amazonico, which runs a programme to rescue and reintroduce manatees, amazing river animals that are well worth looking at here and listening to the stories told the guide, who also explains the effects of the various medicinal plants that grow in the garden created by CREA. There are also a few other animals and some sculptures made for tourists who love to take selfies with strange objects in the background.

And the most unexpected bright spot on the map of Iquitos turns out to be the School of Fine Arts, which we enter out of curiosity and which eventually hosts our watercolour workshop and a lecture on Polish art. The students are happy and Master Emilio, the local lecturer, an artist who creates visionary mushroomy oil paintings, is so appreciative that he invites us to stay at his summer house in the suburb of Santo Tomás. There we spend a very nice, relaxing time away from the hustle and bustle of the city and make friends with some of the local residents, especially Marietita, who, in the comfort of her guest house, prepares a delicious fruit drink – chicha – which she sells opposite the school and which she shares with us generously.

Iquitos

Kolejnego dnia docieramy do Mazán, gdzie rzeka Napo wywija się w łuk, którego łodziom nie opłaca się okrążać, dlatego należy przejechać trójkołowcem na drugi koniec miasteczka (uwaga na naciągactwo, należy uprzednio popytać o cenę transportu), gdzie czeka już przygotowana inna barka, która dotransportuje nas do Iquitos. To będzie naszych kilka pierwszych godzin na Amazonce…

Iquitos to największe miasto świata osiągalne wyłącznie drogą wodną lub powietrzną, niepołączone z resztą Peru żadną drogą (bardzo ciężko byłoby ją wyrąbywać prze gęsty amazoński las), to miasto-bohater jednego z kultowych filmów Herzoga, „Fitzcarraldo” (o czym można poczytać w kilku książkach dostępnych w miejskiej bibliotece; można też przeczesać Iquitos w poszukiwaniu kadrów z filmu), symbol rozkwitu a potem upadku przemysłu kauczukowego, z bajecznymi fortunami kauczukowych baronów, których nazwiska wciąż noszą tutejsze ulice i nieludzkim wyzyskiem miejscowej ludności (zachęcam do zapoznania się z tymi tematami w Museo Etnográfico Amazónico), słowem miasto-legenda, którego odwiedzenie obiecałem sobie dawno temu i w końcu tę obietnicę zrealizowałem.

Chaos portów, barwność targowisk (niesławny dział „magiczny”, gdzie handluje się specjałami z krokodyli, żółwi i innych – teoretycznie chronionych – zwierząt), murszejące kamienice, które próbują godnie się zestarzeć, rozpamiętując swoją świetlaną przeszłość, promenada z widokiem na blaszanodachową, gigantyczną bieda-dzielnicę, zabudowaną ciasno domami na palach, często bez bieżącej wody, zawieszonymi nad bagnami w porze suchej i nad rzeką w porze deszczowej… Jest tu jeszcze duch niedokończonego hotelu, straszący przy centralnym Plaza de Armas, tuż obok Casa de Fierro, mocno zdezaktualizowana stylistycznie metalowa konstrukcja, jest kino oblegane w weekendy, jest ciągły warkot nadmiernej ilości moto-taksówek

za dnia i niepewne oglądanie się za siebie w nocy…

Naszą bazę do eksploracji miasta znajdujemy w Casa del Paucar, oazie względnego spokoju (wściekłe popyrkiwania motocykli i skuterów wciąż są tu słyszalne, bo tych wehikułów jest tu po prostu ponadnormatywnie dużo, samochody trudniej – i drożej – tu sprowadzić). Jest tu bardzo miła obsługa i sporo izraelskiej młodzieży, którą czasem trzeba upomnieć, że nie jest tu sama;)

Miłą niespodzianką jest spotkanie z polską skrzypaczką, mieszkającą w Iquitos, z którą prawie udaje się nakręcić teledysk, ale ostatecznie musimy przełożyć projekt na następny raz… Pod miastem znajduje się Centro de Rescate Amazonico, prowadzące program ratowania i reintrodukcji manatów, niezwykłych zwierząt rzecznych, na które warto tu się pogapić oraz wsłuchać się w opowieści przewodnika, który również objaśnia działanie rozmaitych roślin leczniczych, które rosną w ogródku zorganizowanym przez CREA. Jest tu też parę innych zwierząt oraz kilka rzeźb stworzonych z myślą o turystach uwielbiających selfie z dziwnymi obiektami w tle.

Najbardziej zaś nieoczekiwanym, jasnym punktem na mapie Iquitos okazuje się być Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych, do której wstępujemy z ciekawości i w której ostatecznie organizujemy warsztaty z akwareli oraz wykład o sztuce polskiej. Studenci są wniebowzięci a Mistrz Emilio, tutejszy wykładowca, artysta, tworzący wizyjno-grzybowe obrazy olejne, jest tak bardzo wdzięczny, że zaprasza nas do swojego domku letniskowego na przedmieściach, w Santo Tomás. Spędzamy tam bardzo miły, relaksujący czas z dala od miejskiego zgiełku i zaprzyjaźniamy się z kilkoma okolicznymi mieszkańcami, a zwłaszcza z Marietitą, która w zaciszu swojego gościnnego domku przygotowuje przepyszny owocowy napój – chichę, którą sprzedaje naprzeciwko szkoły i którą hojnie nas obdarowuje.

The day finally arrives when we pull ourselves together and leave the somewhat hot (weather-wise and spirit-wise) Iquitos… In Punchana marina (surrounded by noisy bars and brothels, as well as cheap eateries) we load onto a cargo barge and hang our hammocks on the upper deck, which will be our home for the next four days. After a few hours, it turns out that it will be five days, or more, because we are leaving one day later than planned, but the captain allows us to stay on board for an extra day free of charge. We call at another port in Iquitos in the meantime, then… back to Punchana. We watch the loading onto other barges, onto which animals are sometimes herded – a sort of sadistic Noah’s Ark…. Finally, we set off, leaving Iquitos behind and begin our Amazon cruise…. For a few days, we will gaze at the mysterious jungle passing by, at the noble river, at its sunrises and sunsets, at the villages where, every now and then, we will be able to descend for a moment (or, conversely, the tradeswomen will pop into the barge for a moment, selling all sorts of food specialities), a few times we will spot pink dolphins frolicking in the water, we will have a shower that uses water taken directly from the Amazon, We nourish ourselves with the meagre food prepared by the boat cook (the meat version is miserable, let alone the vegan one, good thing we had stocked up on proper provisions). We chat to fellow travellers – a couple traveling with dogs and cats, in the process of moving house, who have their hammocks next to ours. Hammocks are swinging, books are being read… River life is slowly flowing by until we reach Yurimaguas.

Amazonka

W końcu nadchodzi ten dzień, w którym zbieramy się w sobie i opuszczamy trochę gorące (pogodą i duchem) Iquitos… W przystani Punchana (otoczonej głośnymi barami i burdelami, a także tanimi jadłodajniami) ładujemy się na towarowo-osobową barkę i rozwieszamy nasze hamaki na górnym pokładzie, który będzie naszym domem przez kolejne cztery dni. Po paru godzinach okazuje się, że tych dni będzie jednak pięć, albo i więcej, bo wypływamy z dobowym opóźnieniem, ale kapitan pozwala nam przez ten dodatkowy dzień pozostać na pokładzie, nie kasując za to dodatkowo. Zawijamy w międzyczasie do innego portu w Iquitos, po czym… wracamy z powrotem do Punchany. Obserwujemy załadunek na inne barki, na które czasami zaganiane są zwierzęta – takie mocno sadystyczne Arki Noego… W końcu ruszamy w drogę, zostawiając za sobą smutne Iquitos i zaczynamy rejs Amazonką… Przez kilka dni napatrzymy się na mijaną tajemniczą dżunglę, na nobliwą rzekę, na jej wschody i zachody słońca, na wioski, do których co jakiś czas będzie można na chwilę zejść (albo odwrotnie, przekupki wpakują się na moment do barki, sprzedając różnego rodzaju spożywcze specjały), kilka razy dostrzeżemy fikające w wodzie różowe delfiny, pokąpiemy się w prysznicowni, zasilanej wodą pobieraną na bieżąco wprost z Amazonki, poodżywiamy się marnym żarciem przygotowywanym przez barkowego kucharza (wersja mięsna jest nędzna, a co dopiero wegańska, dobrze, że zaopatrzyliśmy się w odpowiedni prowiant). Zagadujemy do współtowarzyszy podróży – niedaleko nas zakwaterowała się para z psami i kotami, będąca w trakcie przeprowadzki. Hamaki się bujają, książki się czytają… Rzeczne życie płynie sobie powoli aż do Yurimaguas.

At the tourist information centre in Yurimaguas, they are so delighted by the presence of a man from far away that they absolutely have to take a selfie with me. Positive vibes to start our short visit in our last river town. From here, after a brief tour in the centre (promenade under construction, a couple of atmospheric cottages by the water, a market, a square), we head inland.

Yurimaguas

W centrum informacji turystycznej w Yurmiaguas są tak zachwyceni obecnością człowieka z dalekich stron, że koniecznie muszą sobie ze mną zrobić selfie. Pozytywne wibracje na początek naszej krótkiej wizyty w naszej ostatniej przystani rzecznej. Stąd, po krótkim zwiedzeniu miasta (promenada w budowie, parę klimatycznych chatek nad wodą, targowisko, placyk), ruszamy w głąb lądu.

We arrive in Tarapoto, a town which itself does not overwhelm with charm, but it is surrounded on all sides by beautiful forests. One such beautiful foresty spot is the route along the Shilcayo River, and along this route is the headquarters of Urku, a wildlife rehabilitation centre with whomwe become friends and for whom I create photo and video content that will be useful in promoting their activities. This gives us the chance to see a couple of adorable animals up close, take a nighttime tour of the forest (lots of insects and frogs!) and tour some of the surrounding villages that Urku works with, providing training in organic farming and promoting local traditional crafts.

Tarapoto

Dojeżdżamy do Tarapoto, miasta, które samo w sobie nie charakteryzuje się jakimś przesadnym wdziękiem, za to otoczone jest ze wszystkich stron pięknymi lasami. Jednym z takich pięknych leśnych zakątków jest trasa wiodąca wzdłuż rzeki Shilcayo, a przy tej trasie ma swoją siedzibę Urku, centrum rehabilitacji dzikich zwierząt, z którym się zaprzyjaźniamy i dla którego tworzę materiały foto i wideo, które będą przydatne w promocji ich działalności. Dzięki temu mamy okazję obejrzeć z bliska parę przeuroczych zwierzaków, wybrać się na nocny obchód po lesie (moc insektów i żab!) oraz objechać kilka okolicznych wiosek, z którymi Urku współpracuje, organizując szkolenia w zakresie ekologicznego rolnictwa oraz promując lokalne tradycyjne rzemiosło.

Another bus takes us to Pedro Ruiz Gallo, from where, after tough negotiations, we organise a mototaxi to the picturesque village of Cuispes, located on top of a small plateau. Lots of cob houses in different stages of decomposition, lots of little-towny cuteness, which will probably soon be erased by the tourist industry, but for now it is all beautiful and innocent. From Cuispes, the route leads to Yumbilla, one of the highest waterfalls in the world (depending on the methodology, it is ranked differently in the classification, nevertheless it is always in the top 3). A pleasant route, first gravel and then little path through the forest, leading us past several viewpoints until we reach the waterfall, which does not disappoint at all. With our CS hostess, we take a break under the impetuously splashing great column of water and have a picnic. On the way back we manage to hitch a ride on the back of a pickup truck for part of the route to Cuispes. A day pleasantly spent.

Cuispes

Kolejny autobus wiezie nas do Pedro Ruiz Gallo, skąd, po ciężkich negocjacjach, organizujemy mototaxi do położonej na szczycie małego płaskowyżu malowniczej miejscowości Cuispes. Dużo tu ziemiankowych chat o różnym stopniu za(nie)dbania, dużo czystego uroku, na który za chwilę pewnie wykona zamach przemysł turystyczny, ale póki co jest pięknie i niewinnie. Z Cuispes prowadzi trasa do Yumbilli, jednego z najwyższych wodospadów na świecie (zależnie od metodologii, zajmuje w różne miejsca w klasyfikacji, niemniej zawsze jest to ścisła czołówka). Trasa przyjemna, najpierw drogą szutrową, a potem ścieżką przez las, prowadzącą nas przez kilka punktów widokowych aż do wodospadu, który zdecydowanie nie rozczarowuje. Z naszą gospodynią CS-ową rozsiadamy się pod chlupiącą z impetem wielką kolumną wody i urządzamy sobie piknik. W drodze powrotnej udaje nam się złapać stopa na pace pickupa na część trasy do Cuispes. Dzień mile spędzony.

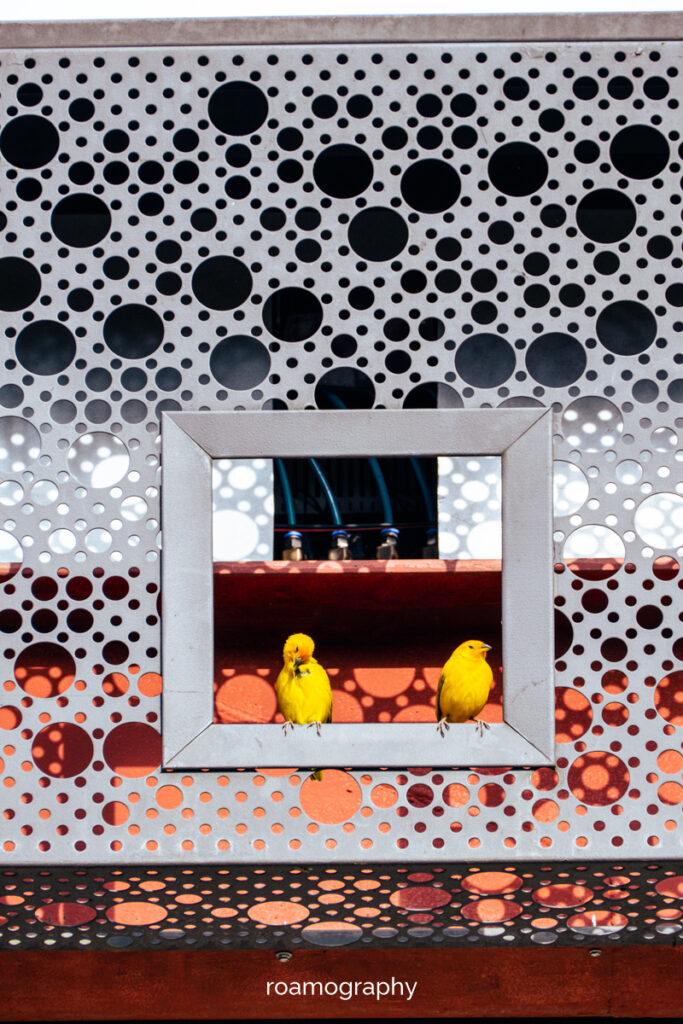

Chachapoyas kindly asks us to take some photos of it, exposing the pretty main square and adjacent streets, as well as all its churches. From the town we set off for our main destination: Karajia.

Chachapoyas

Chachapoyas uprzejmie prosi o zrobienie mu paru zdjęć, eksponując ładny główny plac i odchodzące od niego ulice, kościoły i kościółki. Z miasteczka wyruszamy do naszego głównego celu: Carajía.

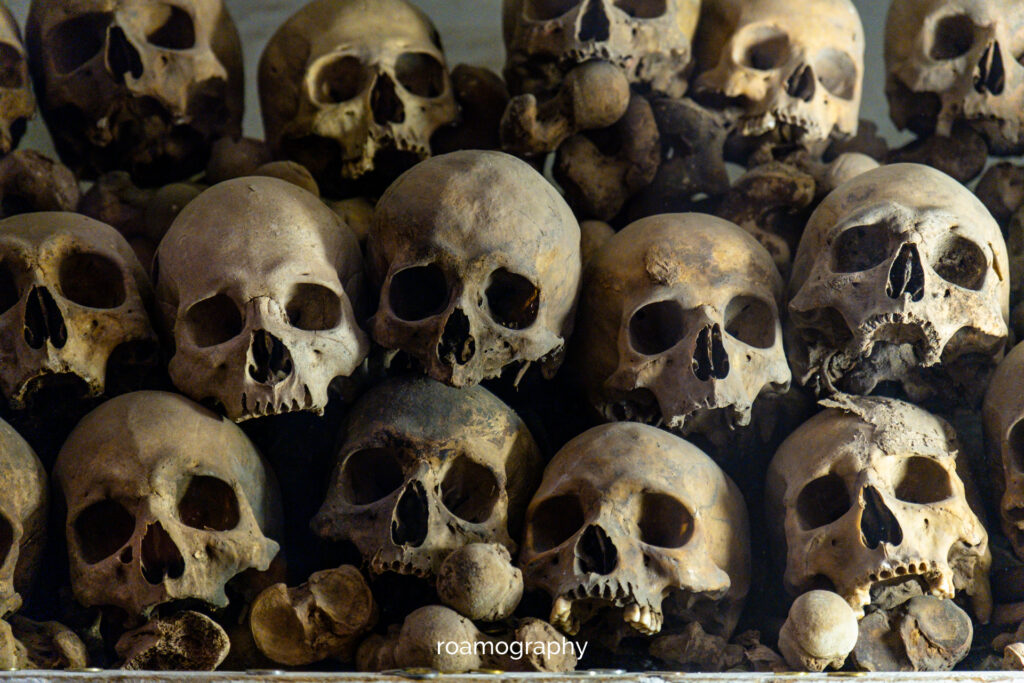

Having passed through Lamud (a small town with a lot of charm) and Luya (a smaller, pleasant town), we arrive in Chocta (an even smaller town, with a tiny, one room museum), from where we set off on foot to the Utcubamba valley, where, hidden on two hard to reach rock shelves, the sculpture-sarcophagi of the mysterious Chachapoyas culture stare into the distance. And they have been staring like this for centuries, in silence, interrupted only from time to time by the shriek of a parrot flying by.

On the way back to the village, we meet chatty and friendly farmers and souvenir makers, from whom we purchase some cool and refreshing chicha – just what we need after several hours of hiking.

Carajía

Zaliczywszy przesiadkę w Lamud (małe miasteczko z dużą dozą uroku) i Luya (mniejsze, sympatyczne miasteczko), docieramy do Chocta (jeszcze mniejsze miasteczko, z tycim muzeum), skąd ruszamy pieszo do doliny Utcubamba, gdzie, ukryte na dwóch trudno dostępnych półkach skalnych wpatrują się w dal rzeźby-sarkofagi tajemniczej kultury Chachapoyas. I patrzą tak od wieków, w ciszy, przerywanej tylko co jakiś czas wrzaskiem przelatującej papugi.

W drodze powrotnej do wioski spotykamy rozmownych i przyjacielskich rolników i pamiątkarzy, od których nabywamy trochę chłodnej chichy, która skutecznie odświeża nas po kilkugodzinnej wędrówce.

We pass one more cool spot here – a viewpoint overlooking the canyon. You can sit here for a while and gaze at the breathtaking views. It is possible to get here and back by public transport, although taxi drivers will try to claim otherwise:)

Cañon del Sonche

Zaliczamy tu jeszcze jedną atrakcję – punkt widokowy na kanion. Można tu chwilę posiedzieć i popatrzeć się na zapierające dech w piersiach widoki. Da się tu dojechać i wrócić transportem publicznym, choć kierowcy taksówek będą próbowali wciskać swój kit:)

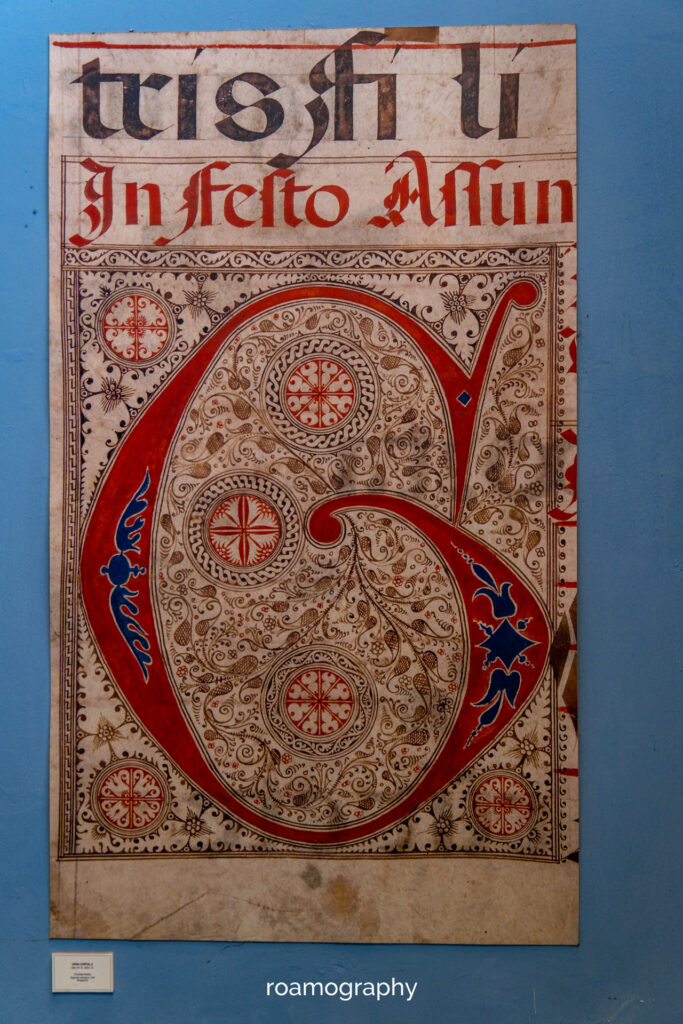

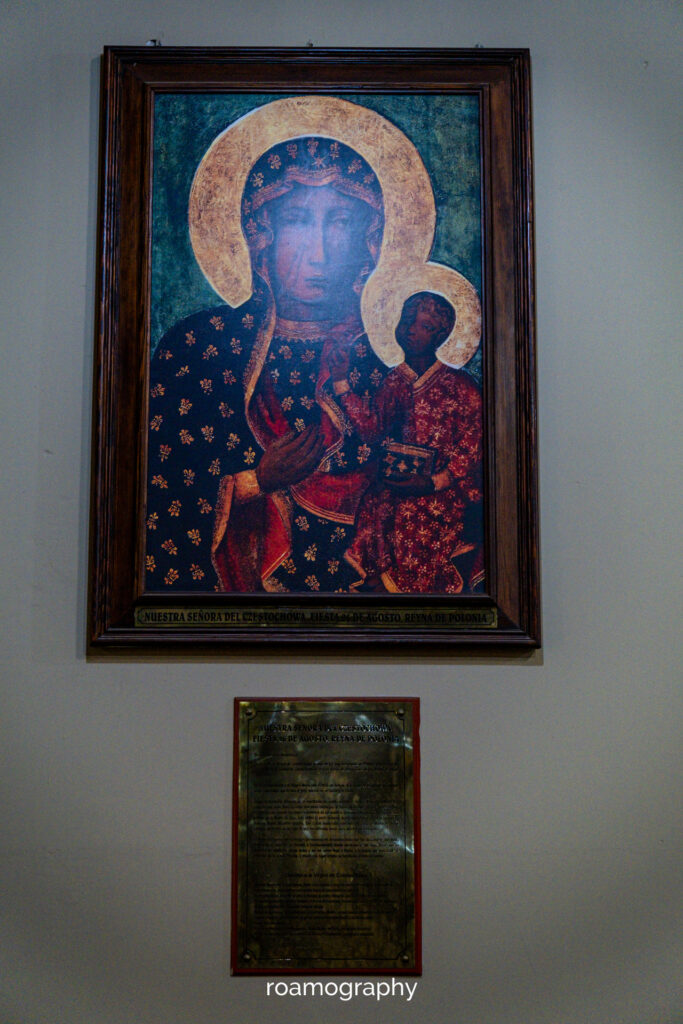

In Cajamarca we pass a long transfer day, during which we do a round of the town and its beautiful churches. There is also a memorial site commemorating the battle between the colonisers and the Incas, during which Atahualca, the local leader, was captured.

And just next to Cajamarca, in Huabocancha, you might want to visit the Virgen de los Dolores cemetery, made in a uniform colourful and funky style. On top of that, there are turkeys walking around the graves. A very cheerful and photogenic place.

Cajamarca

W Cajamarce zaliczamy długi dzień przesiadkowy, podczas którego zaliczamy rundkę po mieście i jego pięknych kościołach. Jest tu też miejsce pamięci, odsyłające do bitwy kolonizatorów z Inkami, podczas której schwytano Atahualcę, lokalnego przywódcę.

A tuż pod Cajamarką, w Huabocancha, warto odwiedzić cmentarz Virgen de los Dolores, wykonany w całości w jednorodnym kolorowo-kulfoniastym stylu. Dodatkowo po grobach spacerują sobie indyki. Bardzo wesołe i fotogeniczne miejsce.

We reach Trujillo, which we skip for now and head straight for the seaside town of Huanchaco, famous for its ‘cane horses (caballitos de totora)’, distinctive boats that have been used for fishing in its original form for centuries (only recently have they started to improve their buoyancy with polystyrene). Tourists (in tolerable numbers) hang around the promenade; a sea lion prowls the grey-stone beach, hoping for an easy snack.

Huanchaco

Docieramy do Trujillo, które chwilowo przeskakujemy i ruszamy wprost do nadmorskiego Huanchaco, słynącego ze swoich „koników trzcinowych (caballitos de totora)”, charakterystycznych łódek, używanych od wieków do rybołówstwa w niezmienionej formie (dopiero od niedawna zaczęto poprawiać ich wyporność styropianem). Turyści (w znośnych ilościach) kręcą się po promenadzie, po szaro-kamienistej plaży kręci się lew morski, liczący na łatwą przekąskę.

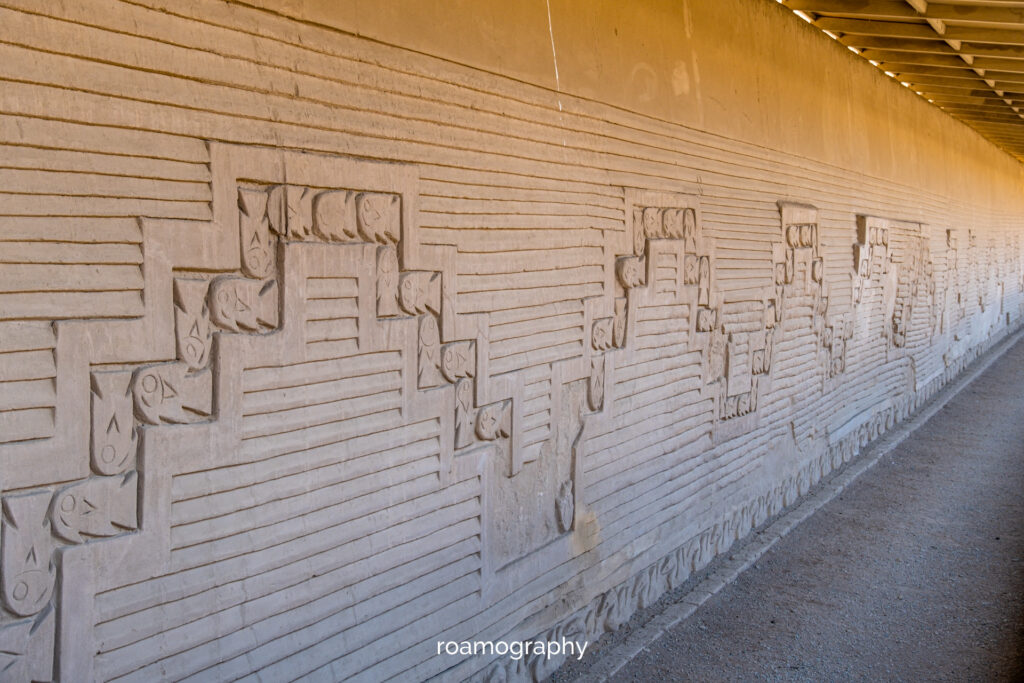

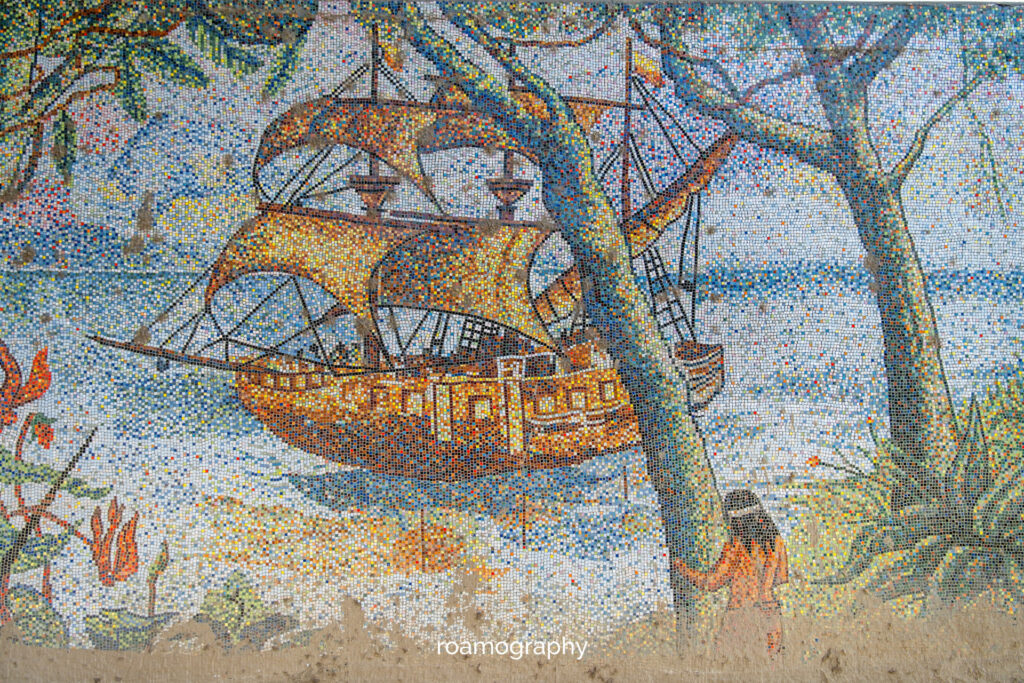

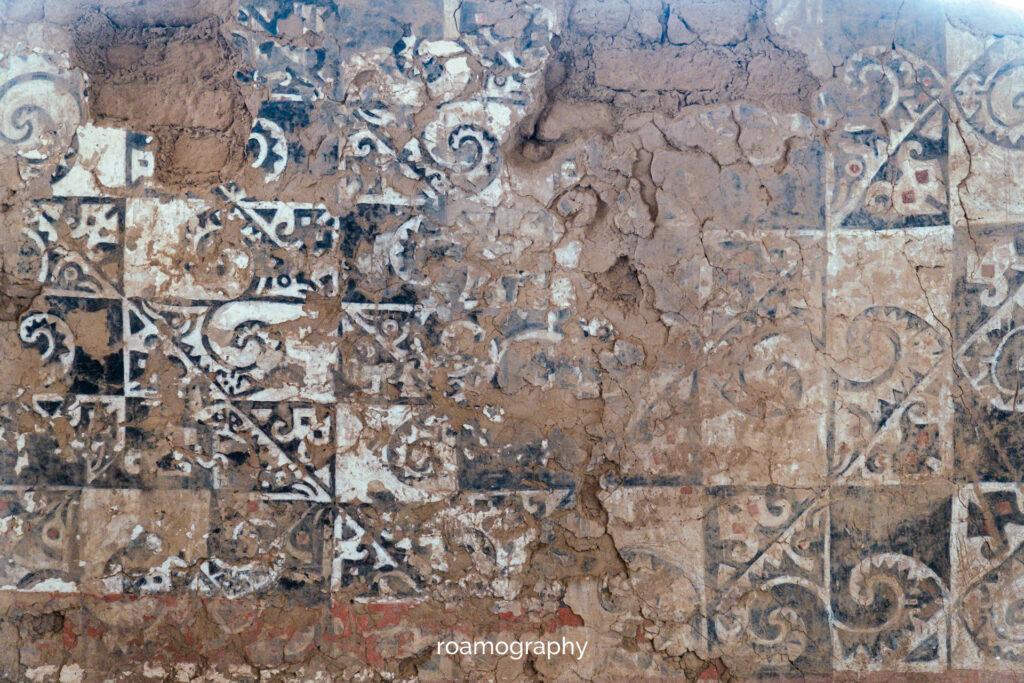

From Huanchaco we are close to Chan Chan, a huge complex of ruins of one of the greatest cities of the pre-Columbian period. Some of the structures have been restored so that we can imagine the decorativeness of this urban unit, built of clay bricks, blasted by the wind and covered with sand for centuries. At another point in the complex, you can also visit a small museum, behind which a path leads to several more buildings.

Chan Chan

Z Huanchaco mamy blisko do Chan Chan, olbrzymiego kompleksu ruin jednego z największych miast okresu prekolumbijskiego. Część struktur odrestaurowano, żeby można było sobie lepiej wyobrazić dekoracyjność tego urbanistycznego molocha, wybudowanego z glinianej cegły, przez wieki wysmaganej wiatrem i pokrytej piaskiem. W innym punkcie kompleksu można też odwiedzić małe muzeum, za którym wiedzie trasa do kilku kolejnych budowli.

In Trujillo we experience a sudden water heater malfunction in the shower – with sparks and an explosion. I wonder what the statistics of electrocution during bathing are in Peru, because judging by the way water heaters are installed and (un)protected in this part of the world, the numbers can be quite high… While walking around the city we get into conversation with a street typist, making official documents. He also happens to occasionally create a bespoke love letter. After a few moments, he brings out from his pocket some sheets of poems he has recently composed. He is such a lovely person to meet…

Apart from this, of course, we tour the city, admiring the well-kept colonial architecture. From Trujillo we also make a foray into Huacas de Moche.

Trujillo

W Trujillo zaliczamy nagłą awarię podgrzewacza wody pod prysznicem – z iskrami i wybuchem. Ciekawe, jakie są w Peru statystki porażenia prądem podczas kąpieli, bo sądząc po sposobie montażu i (nie)zabezpieczenia podgrzewaczy w tej części świata, mogą to być dość wysokie liczby… Podczas spaceru po mieście wdajemy się w rozmowę z ulicznym pisarzem dokumentów urzędowych. Zdarza mu się również czasem stworzyć list miłosny na zamówienie. Po paru chwilach wydobywa z kieszeni kilka kartek z wierszami, które ostatnio skomponował. Uroczy z niego pan poeta.

Oprócz tego, rzecz jasna, zwiedzamy miasto, podziwiając zadbaną kolonialną architekturę. Z Trujillo robimy również wypad do Huacas de Moche.

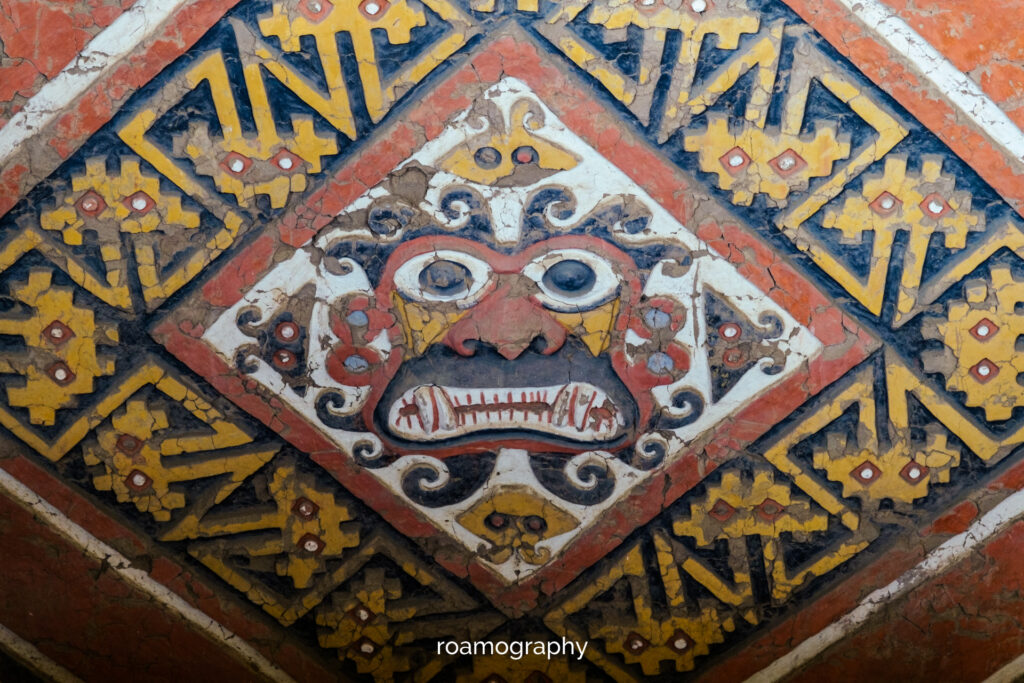

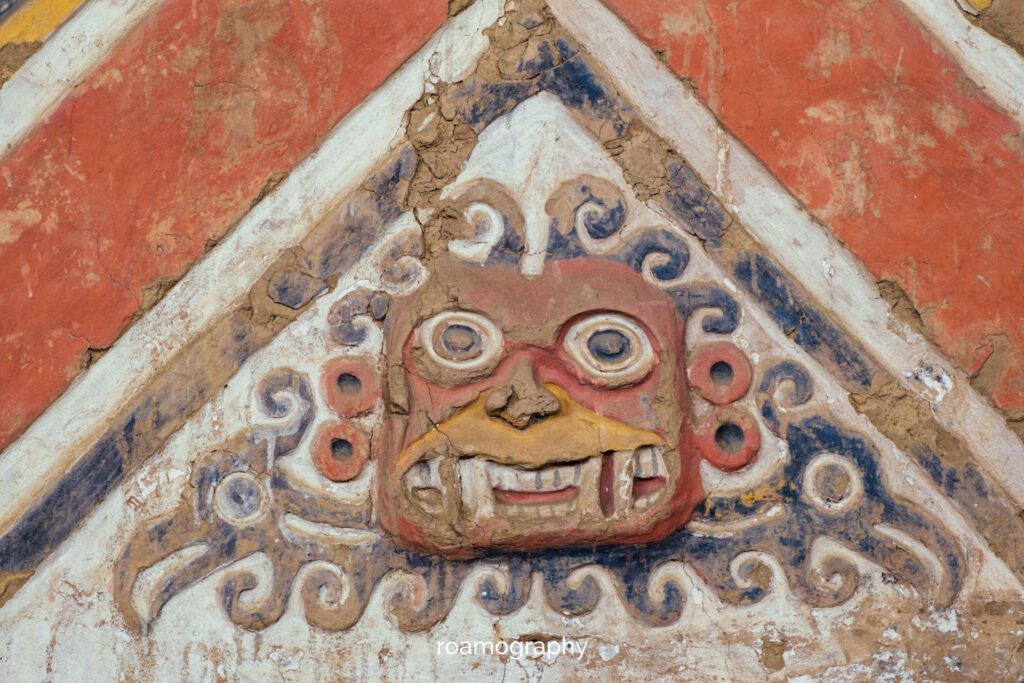

The word huacas means tombs, but in addition to these, we find here the remains of temples of the Mochica culture, altars on which human and domestic sacrifices were made. The peculiar dry climate has made it possible to conserve impressive paintings, full of representations of deities (of which Aiapæc is the most characteristic), as well as animals and the daily activities of the local population. Here we meet a slightly bored archaeologist guarding the site, who tells us passionately about the details and lets us into sectors that probably shouldn’t be walked through. As a result, we come face to face with the creepy-beautiful depiction of Aiapæc.

Huacas de Moche

Słowo huacas oznacza grobowce, ale oprócz tychże, znajdziemy tutaj pozostałości świątyń kultury Mochica, ołtarzy, na których składano ofiary z ludzi i domostw. Specyficzny, suchy klimat umożliwił zakonserwowanie imponujących malowideł, pełnych przedstawień bóstw (spośród których najbardziej charakterystyczny jest Aiapæc), a także zwierząt i codziennych zajęć miejscowej ludności. Spotykamy tu nieco znudzonego strażowaniem archeologa, który opowiada nam z pasją o szczegółach i wpuszcza nas do sektorów, po których chyba nie powinno się spacerować. Dzięki temu stajemy twarzą w twarz ze straszno-piękną podobizną Aiapæca.

From the sea we set off towards the mountains – the Andes have waited long enough for us, it’s time to make friends with them again. We reach the all-trek base of Huaraz, just in time to see a folklore festival. As part of our acclimatisation, we make a round of the town’s surroundings and visit the Wilcahuain – temples and tombs more than a thousand years old, clustered in two small complexes, separated by pleasant villages and groves. We also make our way to the local cemetery, where a merry, boozy party is in progress.

Huaraz

Znad morza wyruszamy w stronę gór – Andy już dość się na nas naczekały, czas się z nimi na powrót zaprzyjaźnić. Docieramy do wszechbazy wypadowej, czyli Huaraz, gdzie załapujemy się na festiwal folklorystyczny. W ramach aklimatyzacji robimy sobie rundkę po okolicach miasta i zwiedzamy Wilcahuian – ponad tysiącletnie świątynki i grobowce, skupione w dwóch niewielkich kompleksach, przedzielonych sympatycznymi wioskami i zagajnikami. Trafiamy też na lokalny cmentarz, na którym trwa wesoła, mocno zakrapiana impreza.

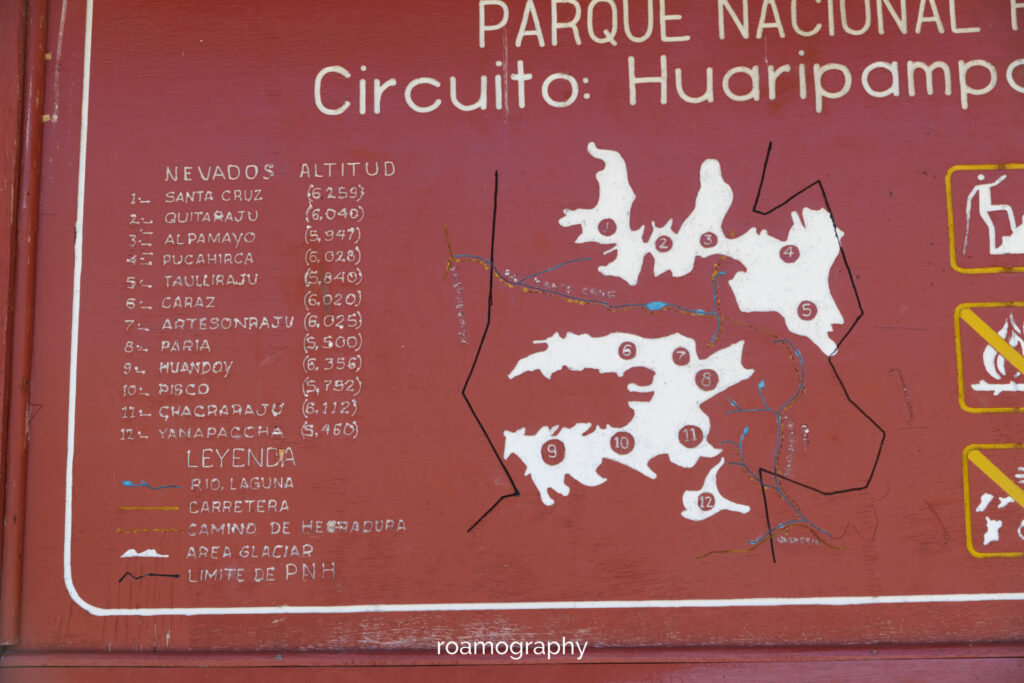

Huaraz, although a pleasant town, is barely the starting point for a variety of trails leading along and across the Andean peaks. And among these trails, perhaps the biggest classic is the Santa Cruz trek, which I decide to do. For three days and two nights, I walk through green valleys and groves, slowly turning into rugged rocky ridges, until I reach Punta Union, which suddenly presents a view that tries to sell all the best that the mountains have to offer in one impressive package: there are snow-capped peaks and a blue lake, scattered boulders, a gorge with another lake in the distance, browns and ochres, greens and whites…. I recommend getting here from the Vaqueria side (change at Yungay, you need to do some price research so you don’t get ripped off), then the stunning landscape appears more suddenly and also the view of Mount Taulliraju doesn’t get as tiresome as when walking from the Cashapampa side. Along the way you find quite a few official (and unofficial, which are usually better) places to pitch a tent, some of which even offer something like a toilet. It’s beautiful and uncrowded, and the frosted sunrises (you will need a thick sleeping bag; they can be rented in Huaraz, too) and picturesque sunsets are unforgettable.

At Cashapampa, I squat down to take a breather (you can also stay overnight in one of the several guesthouses here) and buy a cooling drink from a young girl who dreams of a career as a football star. After drinking as much as I can, I catch a shared taxi to Caraz, which is also worth visiting because of the colourful market that occupies the entire centre of the town.

Santa Cruz trek

Huaraz, choć to całkiem sympatyczne miasto, stanowi ledwie przedsionek do tego, co najważniejsze: trekkingu po rozmaitych trasach wiodących wzdłuż, wszerz i w poprzek andyjskich szczytów. A wśród tych tras, największym chyba klasykiem jest trek Santa Cruz, który postanawiam odbyć. Przez trzy dni i dwie noce wędruję zielonymi dolinami i zagajnikami, powoli przeistaczającymi się w surowo-skalne grzbiety, aż do Punta Union, który nagle roztacza przed oczami widok, w którym próbuje sprzedać w jednym efektownym pakiecie wszystkie najlepsze elementy, które mają do zaoferowania tutejsze góry: są i ośnieżone szczyty, i błękitne jezioro, porozrzucane głazy, wąwóz z kolejnym jeziorem w oddali, brązy i ochry, zielenie i biele… Polecam dotrzeć tu od strony Vaquerii (przesiadka w Yungay, trzeba zrobić rozeznanie cenowe, żeby nie dać się oskubać), wówczas oszałamiający pejzaż pojawia się bardziej nagle a i widok góry Taulliraju się tak nie opatrzy, jak podczas marszu od strony Cashapampy. Po drodze sporo oficjalnych (i zdecydowanie lepszych nieoficjalnych) miejsc na rozbicie namiotu, niektóre z nich oferują nawet coś na kształt toalety. Jest pięknie i nietłoczno, a oszronione wschody (przyda się ciepły śpiwór; można go wypożyczyć w Huaraz) i malownicze zachody słońca są niezapomniane.

W Cashapampie przysiadam na chwilę odsapnąć (można tu też zanocować w jednym z kilku guesthouse’ów) i kupuję napój chłodzący od młodej dziewczyny, która marzy o karierze gwiazdy futbolu. Po opiciu się ile wlezie, łapię shared taxi do Caraz, które też warto zwiedzić, ze względu na urokliwy targ, zajmujący całe centrum miasteczka.

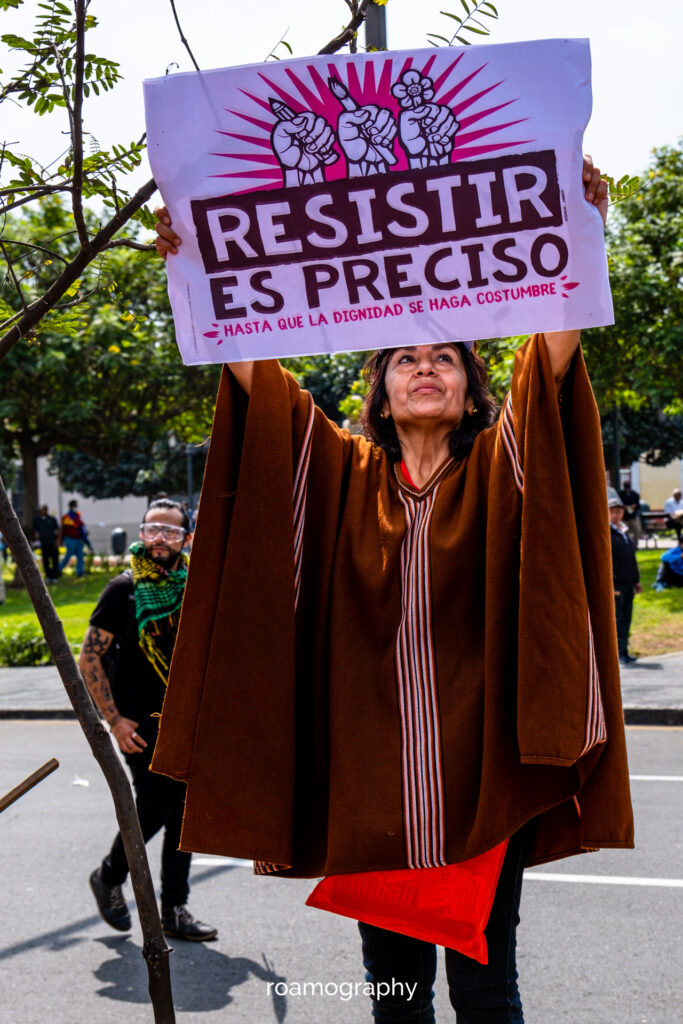

The Peruvian capital greets us with protests against President Dina Boluarte – it’s colourful and loud, and you have to figure out the situation with public transport… Worst of all, the main square, the Plaza Mayor, is partially closed for fear of potentially angry crowds that could do a lot of damage here (the crowds turn out to be peaceful, it’s more the police who like to flex). Anyway, we visit some sights and hit a street of vegetarian pubs, run by a bizarre sect that combines Jesus and aliens in its iconography, spicing it all up with elements of their prophet’s automatic scripture. For dessert, we also enjoy a street costume parade organized by the capital’s police. After this powerhouse of an experience, we head to Gran Terminal Terrestre (the northern station, a rather dodgy area, but cheap accommodation), where we will get on the bus and leave Lima.

Lima

Stolica Peru wita nas protestami przeciw prezydent Dinie Boluarte – jest kolorowo i głośno, trzeba trochę pogłowić się nad transportem publicznym… Co najgorsze, najgłówniejszy plac – Plaza Mayor, jest częściowo zamknięty w obawie przed potencjalnie wściekłymi tłumami, które mogłyby wyrządzić tu sporo szkód (tłumy okazują się być mało wściekłe, to raczej policja lubi tutaj pokazać siłę). Tak czy inaczej, zwiedzamy trochę zabytków i trafiamy na ulicę knajp wegetariańskich, prowadzonych przez przedziwną sektę, łączącą w swojej ikonografii Jezusa i kosmitów, przyprawiając to wszystko elementami pisma automatycznego ichniego proroka. Na deser zaliczamy jeszcze uliczną paradę kostiumową stołecznej policji. Po tej mocy wrażeń udajemy si Gran Terminal Terrestre (dworzec północny, dość podejrzane otaczają go rejony, ale za to noclegi tanie), gdzie pakujemy się w autobus i opuszczamy Limę.

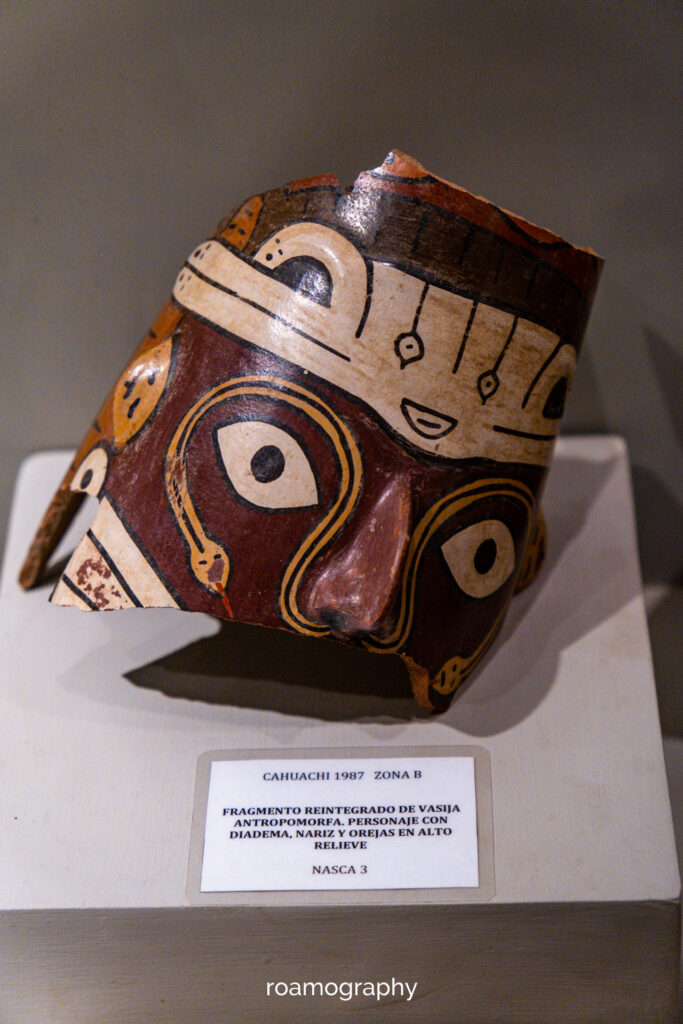

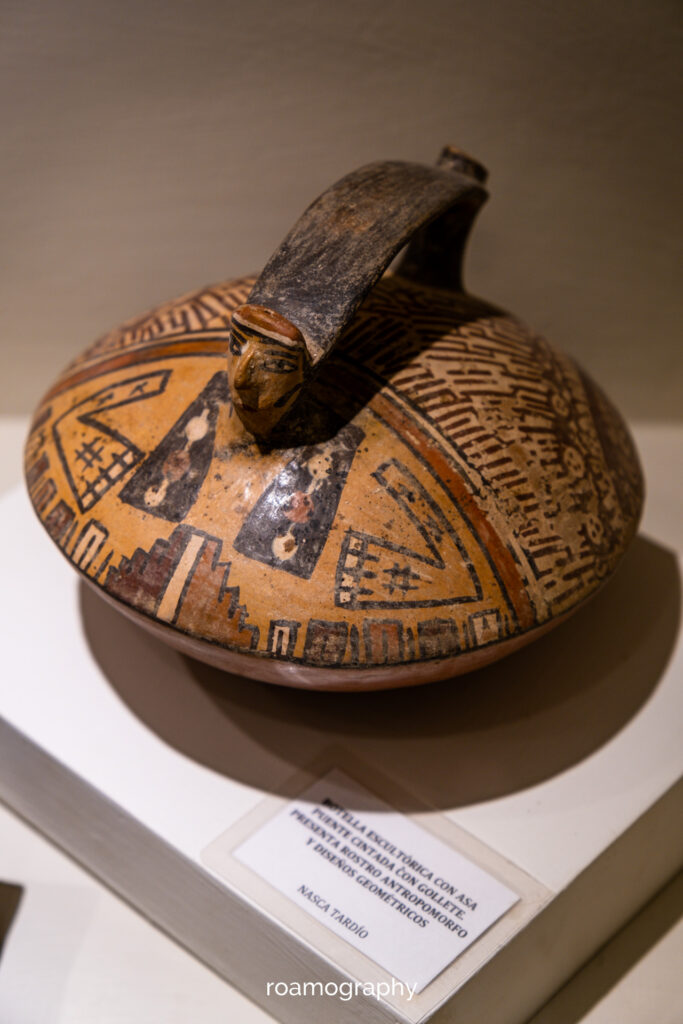

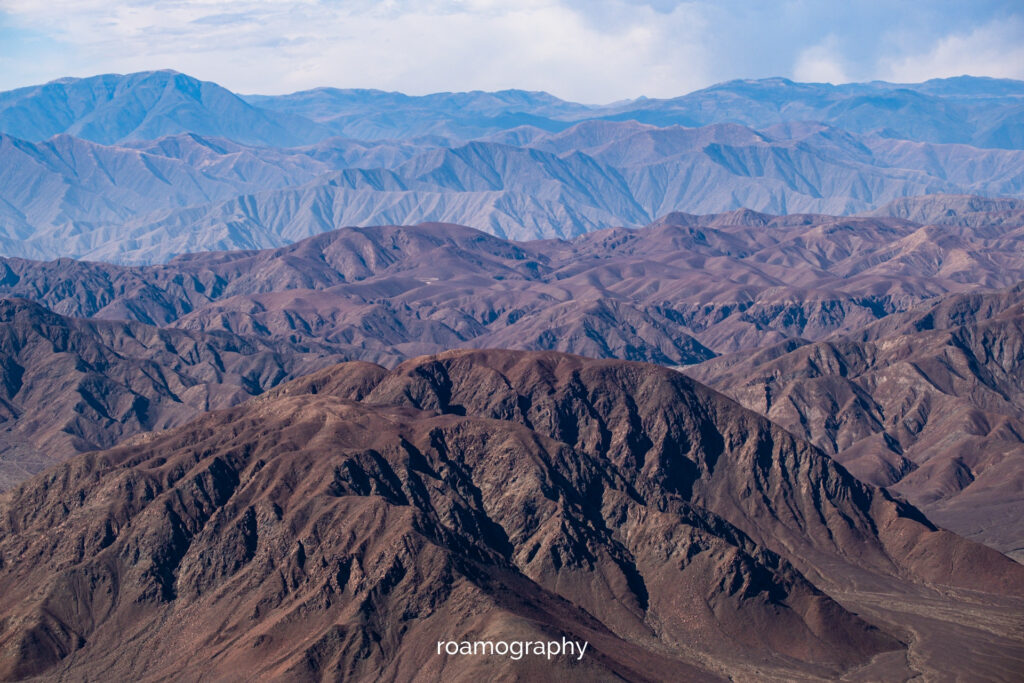

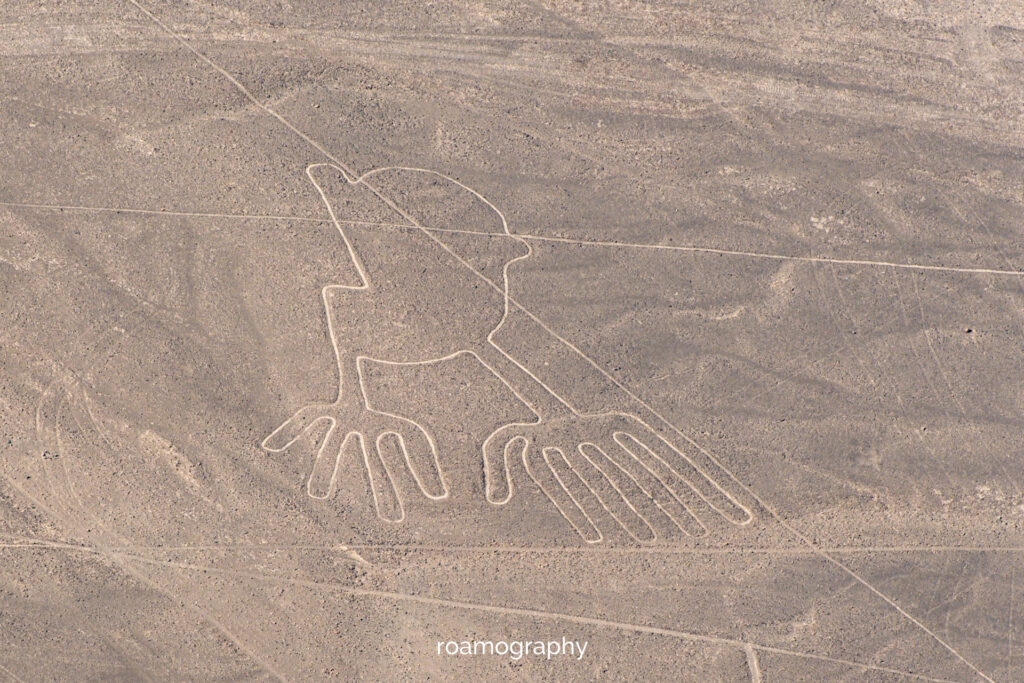

We speed along the coast, brown, sandy and dry as pepper, to an area where this climate has has been helped preserve for centuries, even millennia, some very unique forms of human artistic expression – the mysterious geoglyphs, one of Peru’s most recognisable symbols and one of its main tourist attractions. There are a few other points to tick off in and around the town of Nazca, but they all pale into insignificance when compared to flying over the giant drawings, whose meaning we have still not been able to work out (some practical tips: it is best to go in the afternoon, when the sunlight brings out the depth of the drawings nicely; I also recommend comparing flight prices directly at the airport and trying to negotiate; lighter people have a better chance of bargaining a few dollars; the price includes transport back to the town). Our Cessna is boarded by four other passengers, a pilot and a talkative guide who adds an extra dimension to the spectacular views. The half hour in the air passes very, very quickly; we are already descending, with just a glimpse of the ancient aqueducts and the city skyline… And then, although back on the ground, we remain entranced for a long time.

Bonus tip: if you happen to use Couchsurfing in Nazca, there’s a good chance you’ll be hosted by a star map guide who will bring you to a local mini-museum. Well worth it!

Nazca

Mkniemy wzdłuż wybrzeża, brązowego, piaszczystego i suchego jak pieprz, aż do okolicy, w której klimat ten przysłużył się zachowaniu przez stulecia, a nawet tysiąclecia wyjątkowych form ludzkiej ekspresji artystycznej – mowa, ma się rozumieć, o tajemniczych geoglifach, stanowiących jeden z najbardziej rozpoznawalnych symboli Peru i jedno z jego głównych atrakcji turystycznych. W miasteczku Nazca i okolicach jest jeszcze parę innych punktów do odhaczenia, ale wszystkie one bledną w zestawieniu z przelotem nad olbrzymimi rysunkami, których znaczenia do dzisiaj nie udało się do końca rozpracować (przy okazji parę porad praktycznych: najlepiej wybrać się po południu, kiedy światło słoneczne ładnie wydobywa głębię rysunków; polecam również porównać ceny lotów bezpośrednio na lotnisku i spróbować ponegocjować; lżejsze osoby mają większe szanse utargowania paru dolarów; w cenie zawiera się transport z powrotem do miasteczka). Do naszej Cessny wsiada jeszcze czworo innych pasażerów, pilot i barwnie opowiadający przewodnik, który sprawia, że spektakularne widoki zyskują dodatkowy wymiar. Te pół godziny w powietrzu mija nam bardzo, ale to bardzo szybko, już zniżamy lot, rzucamy jeszcze tylko okiem na starożytne akwedukty i na panoramę miasta… A potem, choć już z powrotem na ziemi, długo pozostaniemy wniebowzięci.

Bonusowa informacja: jeśli zdarzy się Wam skorzystać w Nazca z Couchsurfingu, to istnieje spore prawdopodobieństwo, że podejmie Was gospodarz, który jest przewodnikiem po mapie gwiazd i wkręci was w odwiedziny lokalnego mini-muzeum. Warto!

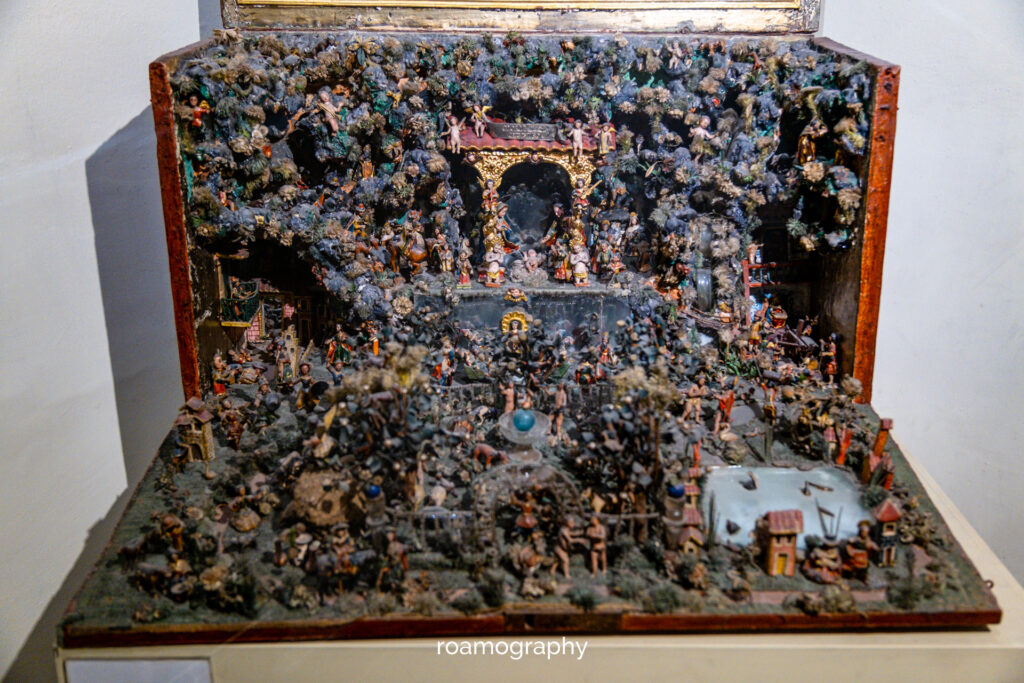

Mentally prepared for the intense touristy nature of this Andean city, we arrive in Cusco with moderate expectations. Yes, we are surrounded by beautiful architecture, especially churches and monasteries; yes, there are lots of places to eat and drink (menus range from local to Israeli to hipster), but the ambiance here has been completely butchered by the tourist industry. And no wonder, this is the travel epicentre of Peru and the gateway to the arch-major attraction: Machu Picchu.

Cusco

Mentalnie zaszczepieni przeciw intensywnej turystyczności tego andyjskiego miasta, przybywamy do Cusco, nie spodziewając się po nim wiele. Owszem, jesteśmy otoczeni piękną architekturą, zwłaszcza sakralną; owszem, jest tu gdzie zjeść i się napić (menu od lokalnego po izraelskie i hipsterskie), ale klimat został tu doszczętnie zarżnięty przez przemysł turystyczny. I nie ma się co dziwić, to epicentrum podróżne Peru i wrota do arcygłównej atrakcji: Machu Picchu.

Depending on your budget, there are various ways to get here – the most expensive is to take the special tourist train, but we choose the economical option – getting by minibus to Hydroelectrica, then a few hours’ walk along the tracks to Aguas Calientes, the base camp for Machu Picchu itself. We walk a bit nervously because, according to the official website, all the nearest entry dates are completely booked, while a couple of locals in Cusco said it was still possible to try… Having reached the town, we submit our application for entry, then make our rounds to find cheap accommodation (no easy task!). The next morning we queue up, full of hope. And we are lucky indeed, but we can only enter on the following day, in the meantime, together with hundreds of other tourists squeezed in the main square, we go through organisational mayhem – the staff don’t know much, moreover they hand out outdated maps of the routes (you have to choose one and pay for it; if you want to take another route, you have to queue up again and pay and pay quite a lot… Moreover, the stressed-out service staff do not speak any English at all, and when shouting out names and surnames from the photocopied passports in their hands, they totally twist them and even confuse the names with the place of birth (without quickly reporting back after such a lame reading, there is no hope of being let into the ticket office). In addition, already in the archaeological park it turns out that the points on the route we have chosen are apparently available, but only at certain times, in the case of some, you have to choose one of two points, and another can only be viewed from a certain angle (finally, being already in the park, I decide to use the “extreme disgust” + “demand to talk to the manager” method, which turns out to be effective and allows us to visit everything, and even turn back on a one-way route). The organisational chaos here can make even the most patient traveller lose their nerve… And this is, after all, one of the wonders of the world, one of the most famous tourist destinations on the planet! The whole system could easily be made a little more comprehensible, if only by putting up an information board describing the rules of the game….

Deep breath in and out. We count to ten in our minds. The nerves are calming down. We can focus on Machu Picchu itself… which is not bad at all, the postcard view is exactly as it should be (only you have to fight a little with the many selfie-takers), the weather also turns out to be kind (nothing could be worse than arriving at the mountain on a cloudy day, especially if you have booked your visit a year in advance), the llamas strolling gracefully – ticked off, the ruins themselves are also quite good.

Here and there, chinchillas crouch in a corner of an old temple. And in the morning, when there are fewer tourists, the walk through the abandoned town is even quite pleasant… And the descent back to the town is relaxing and full of hummingbirds (we descended on foot; for the ascent, however, we took an expensive bus to make the most of the time at the top).

Machu Picchu

Zależne od budżetu, można się tu dostać na różne sposoby – najdroższą jest podróż specjalnym turystycznym pociągiem, my zaś wybieramy opcję ekonomiczną – dojazd busikiem do Hydroelectrica, następnie kilkugodzinny marsz wzdłuż torów do Aguas Calientes, bazy wypadowej do samego Machu Picchu. W drodze towarzyszy nam pewien niepokój, bo wg oficjalnej strony internetowej wszystkie najbliższe terminy wejść są całkowicie zabukowane, z kolei paru lokalsów w Cusco twierdziło, że mimo to można próbować… Dotarłszy do miasteczka, w pierwszym punkcie składamy naszą aplikację o wejście, a następnie robimy obchód w celu znalezienia taniego noclegu (niełatwe zadanie!). Nazajutrz rano ustawiamy się w kolejce, pełni nadziei, iż uśmiechnie się do nas szczęście. I rzeczywiście, uśmiecha się do nas, ale dopiero kolejnego dnia, w międzyczasie wraz z setkami innych, ściśniętych na głównym placu turystów przebrniemy przez organizacyjne piekło – obsługa niewiele wie, ponadto rozdaje nieaktualne mapy tras (trzeba wybrać jedną i zapłacić za nią właśnie; w przypadku chęci przejścia się inną trasą, trzeba po powrocie ponownie ustawić się w kolejce i kolejny raz zapłacić (niemałe) pieniądze… Ponadto, zestresowani pracownicy obsługi nie posługują się nawet w minimalnym stopniu językiem angielski, a wykrzykując imiona i nazwiska z dzierżonych w dłoni kserówek paszportów, przekręcają je niemiłosiernie, a nawet mylą nazwiska z miejscem urodzenia (bez szybkiego zgłoszenia się po takim kulawym wyczytaniu nie ma co liczyć na wpuszczenie do biura biletowego). Dodatkowo, już na terenie parku archeologicznego okazuje się, że punkty na trasie, którą wybraliśmy, są niby dostępne, ale tylko w określonych godzinach, w przypadku niektórych, trzeba wybrać jeden z dwóch punktów, a inny można obejrzeć tylko pod pewnym kątem (ostatecznie, będąc już na terenie parku postanawiam zastosować metodę „ekstremalne obruszenie” + „żądanie rozmowy z kierownikiem”, która okazuje się być skuteczna i umożliwia nam zwiedzenie wszystkiego, a nawet zawrócenie na jednokierunkowym szlaku). Chaos organizacyjny potrafi tutaj wyprowadzić z równowagi nawet najbardziej cierpliwego podróżnika… A to przecież jeden z cudów świata, jedno z najsłynniejszych miejsc turystycznych na całym globie! Można je chyba trochę lepiej ogarnąć, chociażby stawiając tablicę informacyjną, opisującą reguły gry…

Głęboki wdech i wydech. Liczymy w myślach do dziesięciu. Nerwy się uspokajają. Możemy się skupić na samym Machu Picchu… które wcale nie jest złe, pocztówkowy widok jest dokładnie taki, jak ma być (tylko trochę trzeba o niego powalczyć z licznymi selfiarzami), pogoda też okazuje się być łaskawa (nie może chyba być nic gorszego, niż pojawienie się na górze w pochmurny dzień, zwłaszcza jeśli termin wizyty zaklepało się zdalnie rok wcześniej), lamy przechadzające się z gracją – odhaczone, same ruiny też są całkiem w porządku. Tu i ówdzie, w kącie starej świątyni, przycupną sobie szynszyle. A nad ranem, gdy turystów jest nieco mniej, spacer po opuszczonym mieście jest nawet w miarę przyjemny… A zejście z powrotem do miasteczka – relaksujące i pełne kolibrów (schodzimy piechotą; wjazd za to zaliczyliśmy drogim autobusem, żeby maksymalnie wykorzystać czas na górze).

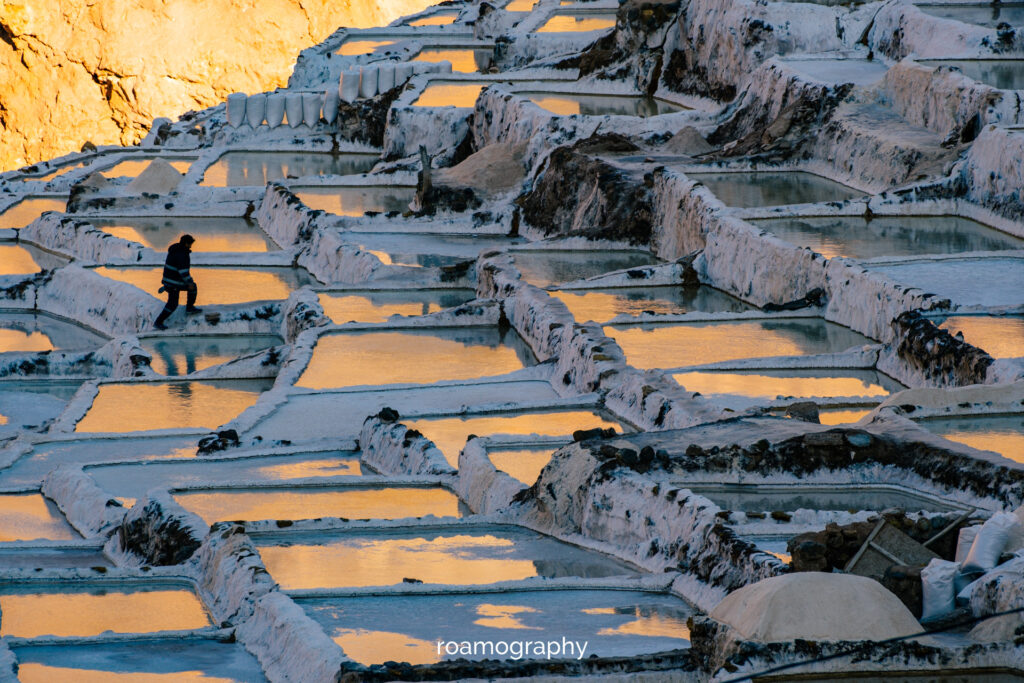

There are other beautiful places to visit in the Cusco area too. One that we strongly recommend is Salineras de Maras, an open salt mine that dates back to pre-Inca times. The families who still exploit their plots have been doing so for many, many generations… Changing buses and cars, we arrive in Maras, a very pleasant town, with restaurant stalls in the central square and, after shoveling in a few calories, we set off towards the valley where Salineras is located. The route is fairly easy, although it’s good to have a map with you so you don’t get lost in the numerous branches that diverge from the main path (especially if, like us, you want to focus on the viewpoints without entering the mine site, not just because there is an entrance fee, but rather because you can only see the scale of the mine from above). We wander along increasingly indistinct paths, with the wall of mountains as our backdrop, some gloomy, some epic, but always majestic and beautiful, until finally, from behind the escarpment, we catch a glimpse of an incredible sight: hundreds, or perhaps thousands, of milky-ochre, cocoa and coffee-ink (from Inka coffee:) puddles, framed by whitewashed salt walls.

In the midst of this amazing organic mosaic, figures of salt miners flit about, tending their fairy plots. We walk from one vantage point to the next, scaring off a few hummingbirds lurking in the bushes, descending lower and lower until we finally stand next to the salt pools themselves (on the lower side, where no one checks any tickets). We descend further into the village, filled with great aesthetic impressions. Here we catch a shared taxi to Urubamba station and return, for the last time, to Cusco.

Salineras de Maras

W okolicach Cusco są i inne piękne miejsca, które warto odwiedzić. Jednym z nich, które zdecydowanie polecamy, są Salineras de Maras, otwarta kopalnia soli, której początki sięgają czasów pre-inkaskich. Rodziny, które do tej pory eksploatują swoje poletka, robią to już od wielu, wielu pokoleń… Metodą kilkubusową docieramy do Maras, bardzo sympatycznego miasteczka, ze straganami restauracyjnymi na placu centralnym i, po wrzuceniu w siebie paru kalorii, ruszamy w drogę ku dolinie, w której mieszczą się Salineras. Trasa dość łatwa, choć dobrze mieć ze sobą mapę, aby nie pogubić się w licznych odnogach odbijających od głównej scieżki (zwłaszcza, jeśli chce się – jak my – skupić się na punktach widokowych, bez wchodzenia na teren kopalni, nie tylko dlatego, że wstęp jest płatny, ale raczej dlatego, że tylko z góry widać skalę tego przedsięwzięcia). Kluczymy po coraz mniej wyraźnych ścieżynkach, za tło mając ścianę gór, niektórych posępnych, niektórych epickich, ale zawsze majestatycznych i pięknych, aż w końcu zza skarpy dostrzegamy niesamowity widok: setki, a może tysiące mleczno-ochrowych, kakaowych i kawo-inkowych (od kawy Inka:) kałuż, obramowanych bieluchnymi solnymi murkami. Pośród tej niesamowitej, organicznej mozaiki, przemykają figurki górników-salinowców, oporządzających swoje bajkowe poletka. Spacerujemy od jednego punktu widokowego do drugiego, płosząc kilka przyczajonych w krzakach kolibrów, schodzimy coraz niżej, aż w końcu stajemy nad samymi solnymi basenami (od dolnej strony, gdzie nikt nie sprawdza żadnych biletów). Schodzimy dalej, do wioski, pełni niezapomnianych przeżyć estetycznych. Łapiemy tu shared taxi do dworca w Urubambie i wracamy, po raz ostatni, do Cusco.

We decide to end our journey in Peru on a high note: we have long dreamed of seeing the condor in flight – it is the largest flying bird in the world with a wingspan of up to three metres! We travel to Limatambo to do just that.

Here we have some difficult negotiations with the taxi drivers (made easier by the fact that we had previously done some research in the town on the subject of fares), until we finally reach an agreement and are given a lift to the entrance of Chonta Canyon. There we meet a US tourist coming down, accompanied by a local ‘guide’ – the North American lady has a sad look on her face because she has not managed to spot a condor… Believing in our luck, we set off towards the viewpoints and after walking for about two hours we reach the last one, where the probability of seeing a condor is the highest. We arrive, sit down and wait. We wait… Five minutes pass, ten minutes, half an hour… And finally it arrives… First we hear the sound of air hitting the outstretched wings, then the giant emerges from a deep valley… Or rather, a giantess, because the first condor to grace us with its presence is a female…. It drifts along for a while, surveying the landscape around it, only to dive behind the mountain a moment later… And then, just a moment later, a male condor arrives, presenting itself in a regal manner, the ruler of the valley, a majestic bird that is increasingly difficult to find in the wild… The show of the disappearance and reappearance of the two birds continues for some time, in absolute silence, interrupted only from time to time by the deep sound of hot air being seized by the wing. Only towards the end of the condor show does a children’s tour group appear, bringing with them a different set of sounds, but by then we are already beginning our return walk.

A bit of magic before we say goodbye to Peru.…

Useful tip: You have the highest chances of seeing the condors around 3-4PM.

Epilogue

Again in Lima, we sort out the souvenir stuff (we’re mainly aiming for ceramic cows, as cows are a standard decorative theme in Peru, being a symbol of prosperity) and find a room just outside the airport, lurking for the plane we don’t have booked. Flight prices at this time are beyond reasonable levels, so we make use of our friend’s friend working for an airline, which results in my first ever experience of flying on a so-called “buddy pass”. “Buddy pass” means a good price, but also having to stand at the counter in the hope that the plane will not be full and there will be a seat left for me. The trouble is that there are a lot of such buddy-pass holders waiting too, so it may not be easy. And indeed, on the first day I return empty-handed. On the second day, too. But the third time’s the charm – not only do I finally make it, but I also get a seat on business class. Phew, it was literally difficult to leave Peru behind this time:)